Discover the Geology of Scotland

Some geological features are so tiny you need a microscope to see them. Others can cover hundreds of miles. Aerial photography might not be much good for the microscopic, but it is ideal for viewing some of Scotland’s largest landscapes. From extinct volcanoes to country-splitting rifts, aerial photographs have been used extensively for mapping areas of geological interest in Scotland. Many of these images are now in the care of the National Collection of Aerial Photography (NCAP).

Glaciers

When discussing geology, one of the hardest things to get your head around is the incredible time spans involved. The most recent activity to shape the rocks beneath our feet is glaciation. Earth has been subjected to a series of glacial periods since the beginning of the Quaternary Ice Age c.2.58 million years ago. The most recent glacial period ended about 11,700 years ago.

The Parallel Roads of Glen Roy are visible on the hillside above the right bank of the River Roy; Collection: Scottish Office APU, Sortie: ASS/62088, Frame: 0093 (10 June 1988)

The area around Glen Roy is packed with proof of how these glaciers shaped Scotland’s landscapes. In Glen Roy itself, the hillsides are marked with a series of horizontal terraces, known as the ‘Parallel Roads of Glen Roy’. These are not in fact roads at all, but all that remains of the shorelines of a great, ice-dammed lake that filled Glen Roy during this final period of glaciation.

As the climate warmed, the ice retreated and the level of the lake gradually dropped, leaving behind the ‘roads’. Glacial action is also responsible for further carving out the Ochil Fault – a step in the landscape caused by one tectonic plate falling while another next to it rises.

The contrast between agriculture and bare hills accentuates the sheer drop of the Ochil Fault Scarp near Tillicoultry; Collection: Scottish Office APU, Sortie: ASS/51288, Frame: 0113 (10 June 1988)

Glaciers also helped create Loch Ness – Great Britain’s largest lake by volume. It sits in the Great Glen, a huge glacial valley that seems to split Scotland in two, from Fort William to Inverness. The Great Glen sits within a much older feature called the Great Glen Fault. This is an enormous geological fracture, where two areas of the Earth’s crust are sliding past each other.

faults

The Great Glen Fault was formed during a complex period of geological activity known as the Caledonian Orogeny, which took place approximately 500-400 million years ago. The ancient continents of Laurentia (which included what is now Scotland), Avalonia (the location of present-day England and Wales) and Baltica collided over millions of years, creating the foundation for the British Isles we know today.

Steep cliffs on the north shore of Loch Ness mark the edge of the Great Glen Fault; Collection: Scottish Office APU, Sortie: ASS/61088, Frame: 0089 (14 May 1988)

The Great Glen was not the only fault created at this time. In the south of the country, the Southern Upland Fault divides the rolling hills of the Southern Uplands from the central Lowland Valley. Between the two, the Highland Boundary Fault – which runs from Arran to Stonehaven – marks the boundary between hard, metamorphic rocks to the north and softer, younger sedimentary rocks to the south.

The line of the Highland Boundary Fault crosses Loch Lomond from Conic Hill in the east through a chain of small islands; Collection: Scottish Office APU, Sortie: ASS 51488, Frame: 0096 (14 June 1988)

ancient rocks

However, none of these features are even close to representing the oldest Scottish geology. The oldest rocks in Scotland are the Lewisian gneisses found in the Outer Hebrides and along the north-west coast of the Scottish mainland. Indeed, they are among the oldest rocks anywhere in the world, dating back an incredible 3,000 million (that’s 3 billion) years.

c.1,100-c.544 million years ago, deposits laid down by huge rivers created Torridonian sandstone on top of the Lewisian gneisses to a depth of 7.5km. In some areas, erosion has carved these later rocks away, revealing the Lewisian rocks below and leaving dramatic Torridonian remnants like the mountain of Suilven (731m).

Suilven rises dramatically from a wild, boggy landscape in Sutherland, with Loch na Gainimh to the east; Collection: Scottish Office APU, Sortie: ASS/61889, Frame: 0238 (19 May 1989)

volacanoes

Another challenging aspect of understanding geological features is the complexity of the processes involved, as rocks can be worn away or raised up repeatedly by numerous agents of change. Great Britain’s highest mountain, Ben Nevis (1345m) is a good example of this.

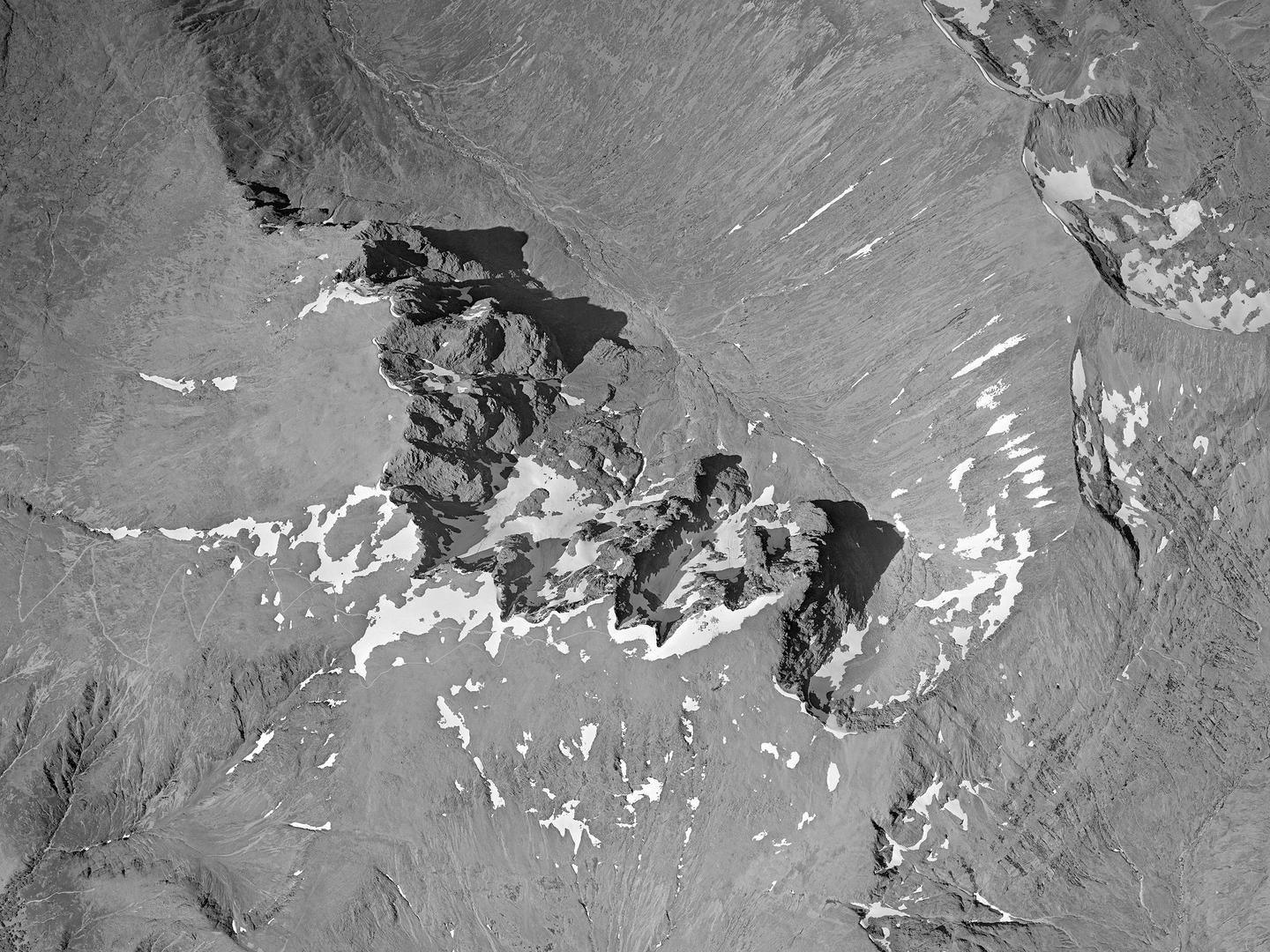

The volcanic peaks and ridges of Scotland’s highest mountain, Ben Nevis; Collection: Scottish Office APU, Sortie: ASS/61888, Frame: 0274 (09 June 1988)

What is now the summit of Ben Nevis started as a part of the ancient Caledonian Mountains (formed c.430 million years ago during the Caledonian Orogeny), which was gradually buried beneath lava and rock from numerous volcanic eruptions. Beneath this area, a magma chamber formed deep within the Earth’s surface, into which the rocks that now form Ben Nevis eventually collapsed. They fell 600m below what was the Earth’s surface, forming a crater called a caldera.

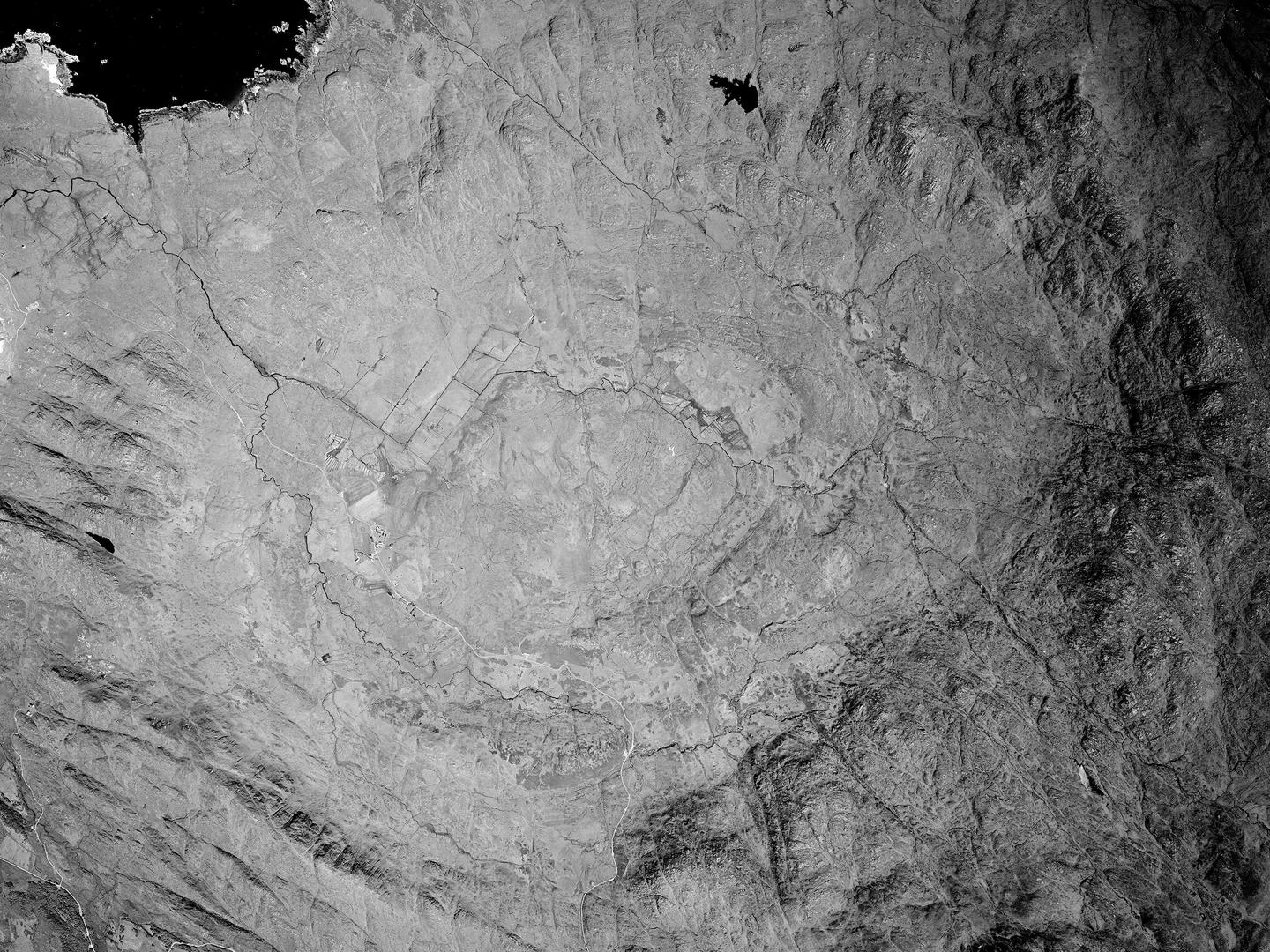

The Ardnamurchan Volcanic Complex in the far west of Scotland, with the rocky dykes visible to the east and south; Collection: Scottish Office APU, Sortie: ASS/61888, Frame: 0161 (09 June 1988)

Over the subsequent hundreds of millions of years, a mixture of erosion and tectonic uplift wore away the surrounding surface, and lifted Ben Nevis’ peak to its current position. Its current shape was carved by the same glacial period that formed Loch Ness. Another example of the complex geology surrounding a caldera is the volcanic complex at Ardnamurchan (formed during the Paleogene period about 23-66 million years ago). Magma was forced up through the rocks surrounding the collapsed magma chamber - the caldera - creating geological formations known as dykes.

Edinburgh Castle on its crag, with the ‘tail’ of the Royal Mile to the right; Collection: Simmons Aerofilms Ltd., Sortie: CLY/8803, Frame: 0762 (07 January 1988)

scottish icons

This combination of volcanic activity and glaciers has helped shape some of Scotland’s most iconic landscapes, including the rocks of Edinburgh and Stirling Castles. They are both built on volcanic plugs, cores of igneous rock formed when magma hardens within the vent of a volcano.

Their distinctive shapes – the steep peak surmounted by the castle, with a gentle ridge leading away – are classic examples of crag-and-tail formations. These are created when a glacier passes over a resistant rock formation like a volcanic plug (the crag), eroding the surrounding softer rock except the area sheltered by the crag (the tail).

Stirling Castle Rock, with steep cliffs to the west and the ‘tail’ running to the south; Collection: Scottish Office APU, Sortie: MER/024/76, Frame: 0149 (08 May 1976)

It is not always easy to see or understand the fascinating, complex geology beneath our feet. However, with the help of aerial photography, we can get a better idea of the amazing processes that shaped the Scotland we live in today.

Ben Reiss, NCAP Collections Manager

Find out more about the collections featured in this article.